Drying is one of the biggest operating costs in a plastic recycling line. The decision is not “centrifugal dryer vs hot air.” It is how far you need to push moisture down before your next step (bagging, extrusion, pelletizing).

This guide explains how energy input differs between mechanical dewatering (spinning off bulk water) and thermal air drying (evaporating water), plus a simple way to estimate energy by the amount of water you remove.

Quick Takeaways

- Use mechanical dewatering first; thermal drying is what gets expensive because you must evaporate water.

- “Dry enough” depends on the polymer and your next process step; don’t over-dry unless the spec demands it.

- Track moisture at discharge and kWh/ton; the best dryer setup is the one that hits spec with stable throughput.

Related Energycle references: – Centrifugal dryer for recycling applications – How centrifugal dryers work (clear guide) – Ultimate guide to thermal drying machines in plastic recycling

The Physics of Dewatering

- Mechanical Drying: Relies on kinetic energy (centrifugal force) to physically separate surface water from plastic flakes. This is highly efficient for removing bulk water but cannot remove surface moisture bound at a molecular level.

- Thermal (Hot-Air) Drying: Uses heat + airflow to evaporate water. This is necessary for final polishing but requires significantly more energy to undergo the phase change from liquid to gas.

Note on wording: “air drying” can mean ambient drying (no added heat) or hot-air drying (heated air). In recycling lines, the “final polish” stage is usually heated-air drying because ambient air rarely reaches low, stable moisture at industrial throughputs.

Mechanical Centrifugal Dryers: High Impact, Low Cost

Located immediately after the washing line, the centrifugal dryer is the “heavy lifter.”

Operational Principle

Wet flakes enter a calibrated rotor spinning at high RPM (typically 1200-1500 RPM). The material is accelerated against a perforated screen. Water passes through the screen, while dry flakes travel upward to the discharge.

Energy Profile

- Primary Input: AC Motor (typically 45kW to 90kW for a 1-ton/hr line).

- Efficiency: A mechanical dryer can reduce moisture from 30% down to approximately 2-3%.

- Why it saves energy: To remove water by evaporation, you must supply latent heat. Spinning removes water without paying that “phase-change” energy cost.

Benefits: * Instantaneous moisture reduction. * Small physical footprint. * Removes contaminants (fines/paper) along with water.

Thermal Hot-Air Drying: The Final Polish

Often called “hot air flash drying” or “spiral drying,” this stage typically follows mechanical drying to achieve final product specs.

Operational Principle

Pre-dried flakes are transported through a long, insulated pipe system using high-velocity hot air. The air is heated via electrical resistors, gas burners, or steam heat exchangers.

Energy Profile

- Primary Inputs: Blower Motor (transport) + Heating Elements (evaporation).

- Efficiency: Reduces moisture from ~3% down to <0.5%.

- Why it costs more: Evaporating water requires latent heat. At 100°C, water’s enthalpy of vaporization is about 2,257 kJ/kg (value varies with temperature).

Benefits: * Achieves very low final moisture levels fit for extrusion. * Gentle handling (no mechanical wear on flakes).

Where Ambient Air Drying Fits (and Where It Doesn’t)

Ambient air drying can look “cheap” on paper (no heaters), but it is usually limited by: – Long drying times and large floor area – Weather/season variation (unstable final moisture) – Dust/contamination risk while material is exposed

In practice, ambient air drying may be acceptable for temporary draining or non-critical storage, but it rarely replaces mechanical + thermal stages when you need repeatable moisture for extrusion.

Strategic Combination for Efficiency

Relying solely on thermal drying is economically disastrous; relying solely on mechanical drying is insufficient for high-quality extrusion.

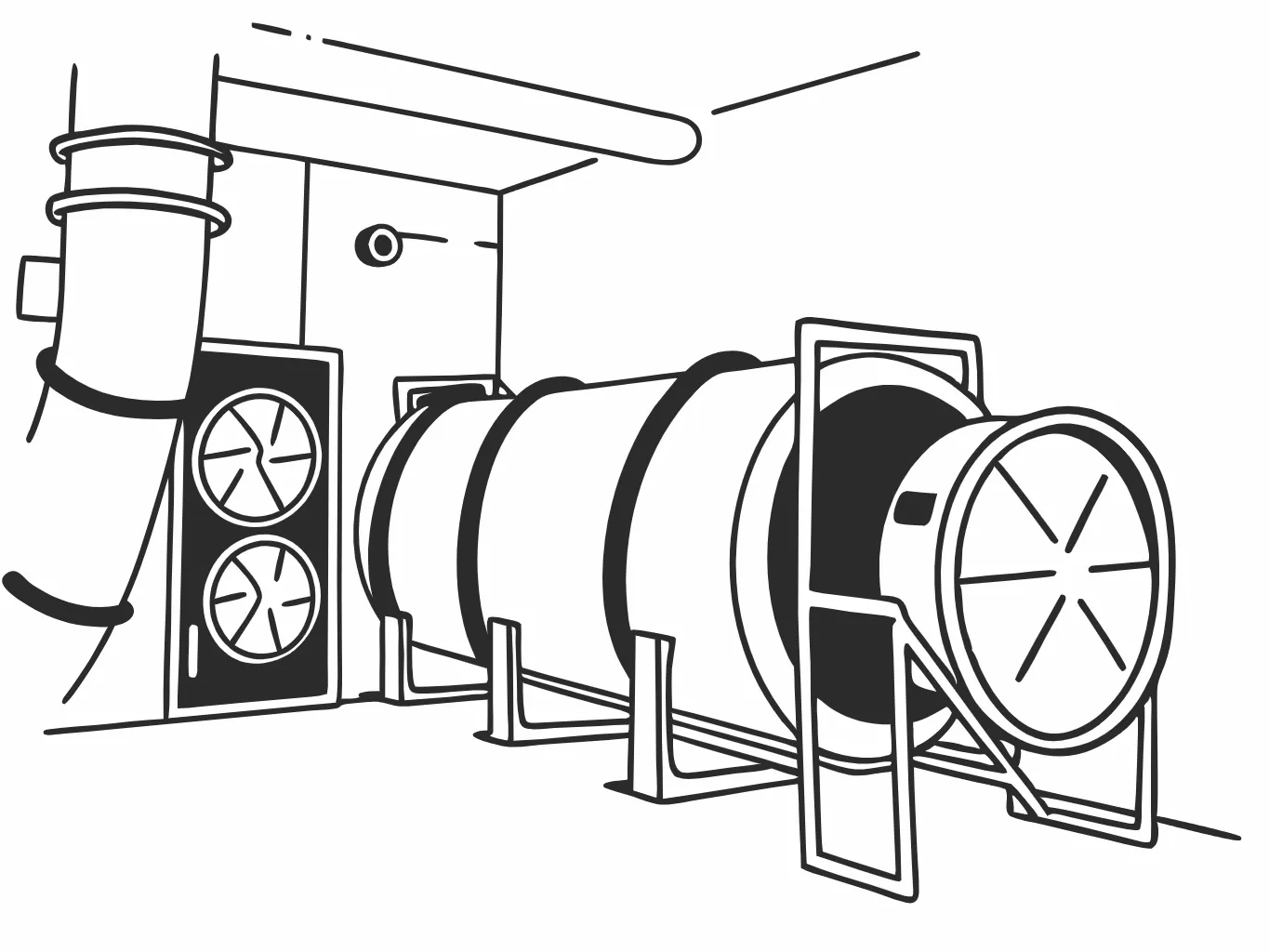

The “Hybrid” Approach: The most energy-efficient recycling lines use a multi-stage approach: 1. Stage 1 – Mechanical: Two centrifugal dryers in series. The first removes 80% of water; the second gets it down to roughly 2-3%. 2. Stage 2 – Thermal: A final hot air spiral pipe system typically requires only a small temperature delta (e.g., 60-80°C) to flash off the remaining surface moisture.

What Moisture Target Do You Actually Need?

Use these as practical starting points; your buyer spec and polymer behavior are the final authority.

| Downstream step | Typical moisture target | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Bagging / storage of washed flakes | ~2% to 5% | Prevents dripping and reduces clumping; usually achievable with good dewatering |

| Extrusion / pelletizing (general) | Often <1% (commonly <0.5%) | Reduces steam/bubbles, pressure instability, and surface defects |

| High-sensitivity products (case-dependent) | Lower targets may be required | Some polymers and end uses demand tighter moisture control and additional drying steps |

Energy Cost Comparison (Simple, Directional Example)

Assume you process 1,000 kg/h of dry plastic.

| System Type | What it does | Main energy driver | Directional takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Only | Removes bulk water after washing | Motor power (kW) and load | Low-cost drying, but may not hit extrusion-grade moisture |

| Thermal Only | Evaporates most water without dewatering | Latent heat of vaporization + blower power | Very high energy if you try to evaporate “bulk” water |

| Optimized Hybrid | Dewater first, then evaporate the last fraction | Small thermal load after dewatering | Best balance of spec, stability, and operating cost |

A Simple Energy Estimate (Use for Back-of-the-Envelope Planning)

If your line needs to evaporate W kg of water per hour, the theoretical minimum heat input (not including losses) is:

Energy (kWh/h) ≈ (W × 2,257 kJ/kg) ÷ 3,600

That means evaporating 1 kg of water is about 0.63 kWh at the theoretical minimum. Real systems use more (heat losses, exhaust air, imperfect heat transfer). For planning, many plants assume a multiplier (often ~1.5× to 3×) depending on dryer type and heat recovery.

Example (directional): If material after a centrifugal dryer is ~3% moisture and you need ~0.5% for extrusion, the remaining water to remove might be on the order of ~25–30 kg/h per 1,000 kg/h of dry plastic, which already implies ~16–19 kWh/h theoretical heat before losses and blower power.

Why “thermal only” gets expensive fast: If washed material enters drying at ~30% moisture and you still need ~0.5%, you may be evaporating hundreds of kg/h of water per 1,000 kg/h of dry plastic—directionally 250+ kWh/h theoretical heat before losses.

Common Reasons Plants Spend Too Much on Drying

- Skipping dewatering: Sending “dripping” flakes into hot air drying forces the heater to do work a centrifuge should do.

- No moisture measurement: Operators adjust by feel, which usually means over-drying (wasted energy) or under-drying (quality failures).

- Screen and airflow neglect: A blinded screen or restricted exhaust reduces dewatering performance and makes the thermal stage work harder.

Special Case: Film Lines (Squeezer vs Centrifugal)

If you are drying washed film, mechanical dewatering often uses a squeezer (rather than only a centrifugal dryer) to remove water and densify film before thermal polishing. For a reference point, see Energycle’s plastic dewatering drying centrifugal thermal squeezer and plastic film squeezer technology.

Conclusion

Mechanical dryers remove bulk water efficiently; thermal drying is the finishing step when the product spec requires it. If you size and operate the mechanical stage correctly, you can usually shrink the thermal load and stabilize final moisture.